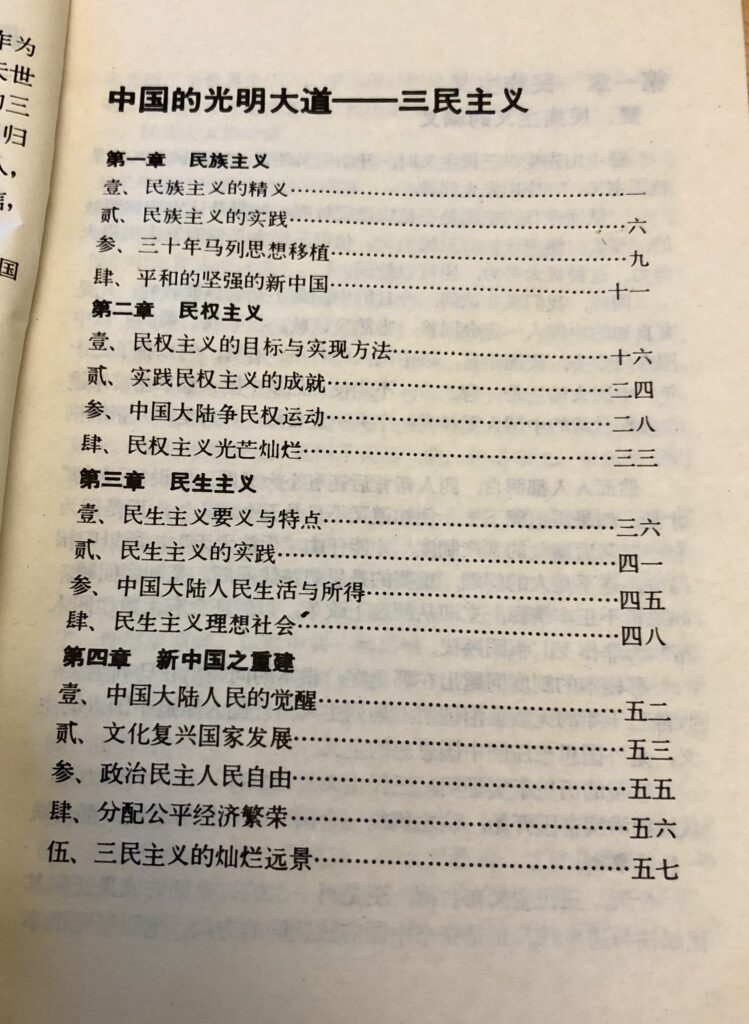

Our book collection holds quite a number of leaflets, pamphlets and interesting paraphernalia, and today we present on of these. At first glance it could have been printed in Beijing and part of showing how modern the city had become after the policy of ”Four modernizations” 四个现代化, first started in the 1960s and then revived late 1970s. But anyone knowing Chinese sees directly that there is something strange, as the title is ”China’s Glorious Way – the Three Principles of the People” 中国光明大道 三民主义. The Three Principles of the People (full Chinese text here) were not formulated by Mao Zedong but by Sun Yat-sen 孙逸仙 (Sun Zhongshan 孙中山 1866-1925), the ”Father of the Nation” 国父 and first president of the Republic of China. The photo on the cover shows Taipei 台北 (Taibei in pinyin), not Beijing, but the Chinese characters are all simplified as if printed in the PRC. They are not, however, as this is Taiwanese propaganda material.

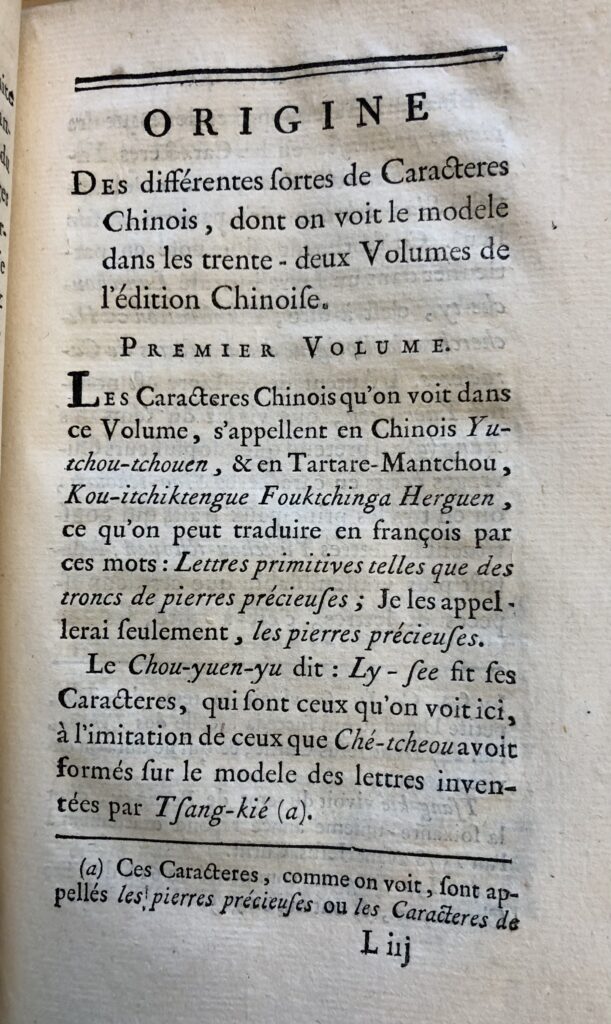

The pamphlet is not dated, but should be from the early 1970s, as Chiang Kai-shek is still evoked, he died in 1975. The language is very similar to PRC propaganda as we can see on one of the images: ”Chairman Chiang’s [Kai-shek] important points on the Three Principles of the People” 蒋主席有关三民主义的重要提示. The exact same phrase is still used when Chairman Xi Jinping has something important to tell… Calling it the ”Glorious Way” is also well chosen as that phrase was often used during the Cultural Revolution. Item three under the first chapter talks about ”transplanting 30 years of Marxist-Leninist thought” 三十年马列思想移植. The fourth chapter is about the ”rebuilding of New China” 新中国的重建, a sharp play with words as ”New China” and ”rebuild” were exactly the terms used by Mao Zedong in 1949.

If the reader still had not quite understood where the pamphlet came from, he or she would get a lead from the last inner page where the distinct logo of Central Daily 中央日報 is displayed. Central Daily was the major Kuomintang newspaper, founded in 1928 and long a leading Chinese newspaper. After Taiwan democratised in the 1990s and Kuomintang lost influence the newspaper lost impact and sales, and paper circulation was stopped in 2006, web presence ended in 2018.